Music of J. S. Bach

(1685-1750)

Fourteen Canons on the Bass Line of the Goldberg Variations

~ ~ ~

The Art of Fugue

Simple fugues (in four voices)

Contrapunctus I

Contrapunctus II (harpsichord solo)

Contrapunctus III: original subject inverted

Contrapunctus IV: subject inverted

Stretto fugues (overlapping subjects):

Contrapunctus V: subject upright and inverted

Contrapunctus VI: “in stile francese”

Contrapunctus VII: subject upright, inverted, in diminution and augmentation

Contrapunctus VII: triple fugue in three voices

Contrapunctus IX: double fugue in four voices

Contrapunctus X: double stretto fugue (harpsichord solo)

Triple Fugue

Contrapunctus XI: Triple fugue in four voices

(on themes and fragments from the previous fugues)

~ ~ ~

Canonic Fugues (in two voices)

Canon at the octave

Canon at the 10th

Canon at the 12th

Canon in augmentation and contrary motion

Mirror Fugues

Contrapunctus XII in three voices

Contrapunctus XIII (literal inversion of Contrapunctus XII)

Contrapunctus XIV, in four voices

Contrapunctus XV (literal inversion of Contrapunctus XIV)

Unfinished Quadruple Fugue (the third subject spells B.A.C.H.)

~~~

Chorale Prelude: Vor deinen Thron tret ich hiermit (Before thy throne I now appear)

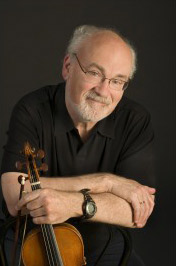

Daniel Stepner, baroque violin Jason Fisher, baroque viola

Laura Jeppesen, viola da gamba Loretta O’Sullivan, baroque cello

Christopher Krueger, baroque flute Stephen Hammer, baroque oboe and oboe da caccia

Andrew Schwartz, baroque bassoon Peter Sykes, harpsichord

The Fourteen Canons

In 1974, a previously unknown manuscript by Bach surfaced in a private collection in France, and it shook up the musicological world. It was a single sheet of paper on which fourteen canons were sketched out as enigmatic puzzle-pieces. They were in abbreviated form, requiring the musician who wished to hear the canons — either played by instruments, or on the keyboard, or in his/her head – to follow written clues (some verbal, some symbolic) as to where subsequent entries of voices were to be made in order to realize the puzzle musically. The essential “tune” was the bass line of the Goldberg Variations (BWV 988). The first four canons were simply that bassline in canonic counterpoint with itself – right side up, upside down, backwards, and backwards and upside down. Subsequent canons invent new counterpoints to the bass line, also realized in canon, at various intervals of time, and in both diatonic and chromatic styles. The penultimate canon is in six voices, and the final canon in four voices at three different levels of speed – something one hears developed further in The Art of Fugue. The canons are all presented as “perpetual canons,” meaning that each could be performed ad infinitum (think: “Row, Row, Row your Boat”). The performance tonight links them together in arbitrary fashion, but with a mind to proceeding from the most simple to the most complex – a habit Bach himself relished in many of his works.

These canons are the sort of thing that probably occupied Bach constantly. They represent his need and, no doubt, his delight in realizing all combinatorial possibilities of any given musical phrase. In that sense he was a conceptual genius. As one musicologist put it: Mozart, Beethoven and Brahms used counterpoint masterfully, but Bach thought in it.

The Art of Fugue

Perhaps no other work in all of Western music makes more out of virtually nothing. More precisely, no work creates such a grand, many-faceted, truly awesome musical edifice out of the simplest of building blocks. That irreducible germ is simply the outline of a D minor triad, followed by a short, stepwise scale fragment. During the course of the fifteen fugues and four canons that make up The Art of Fugue, there are progressive changes to that short subject – changes in the internal musical intervals, rhythm, speed, implied inflection, etc. Yet those variants never change the subject’s essential identity. The subject is sometimes turned upside down, and often overlapped with itself; its disjunct intervals are sometimes filled in with connective tissue — sometimes diatonic (“white-key” notes), sometimes chromatic (both white and black keys, sequentially) — and yet one always senses the subject “behind the scenes” because of its essential simplicity. The gradual mutations in the subject unlock possibilities of harmonic excursions to remote key areas, which Bach makes bold use of, though he always returns home to D.

With repeated hearings, the attentive listener will recognize the transformed subject and sense some of the implications that those transformations have for the burgeoning contrapuntal possibilities of which Bach takes full advantage. Playing one or another of the lines in this work gives the player a sense of being inside Bach’s mind, a mind that seems to see every potential for variation and combination in the most basic of ideas.

One of his more mind-expanding inventions is the simultaneous statement of the subject on three time-levels, most obviously in Contrapuncti VI and VII, where one hears the subject at the original speed in one voice, twice as fast in another, twice as slow in yet another, all at the same time. These roles are interchangeable and often one or more of these strands are heard upside down. The listener scans among the voices and is suspended in a multi-dimensional universe full of delightful musical play.

As the work progresses, one hears new and increasingly identifiable countersubjects – melodies that Bach uses to harmonize with the subject – that take on their own life of new contrapuntal possibilities. In the double and triple fugues, they become subjects to their own formal, discrete fugues before recombining with the original subject in full contrapuntal development. This is true also of the unfinished quadruple fugue, whose third fugue has as a subject Bach’s musical signature: B flat, A, C, B natural (H in German lettering practice).

In the original, posthumous edition (1751) there is a printed comment where the music stops which reads: “While working on this fugue, in which the name BACH appears in the countersubject, the author died.” And so The Art of Fugue was thought for more than two centuries to be his final work. The reality is more interesting: though Bach was indeed working on it shortly before his death and preparing it for publication, he had begun the work at least nine years before. Watermarks and different orderings of the fugues in his manuscripts attest to this. It seems he was continually touching up and adding to it. One version of the collection, now datable to about 1741, consisted of twelve fugues and two canons. The later version now had three more fugues and two more canons. One can somehow imagine – given the mind-boggling contrapuntal invention in works like the Musical Offering (composed in about two weeks in 1747) that he might have added still more canons and fugues to The Art of Fugue, had he lived longer.

Bach scholar Christoph Wolff makes a compelling argument in various essays and in his magisterial biography that Bach did in fact complete the final fugue. The very notion of a quadruple fugue that had a convincing, organic ending — to the whole cycle as well as itself! — suggests that he would have had to work out the complex, valedictory combination of four simultaneous themes, including the original subject, in advance. His final illness and passing created confusion in his papers and manuscripts, it seems, and his family — particularly his faithful son Carl Philip Emanuel Bach — could not find the intended “solution” to the final fugue among the drafts and sketches. C.P.E. Bach therefore published the work with a questioning half-cadence – a sort of musical semi-colon – at the work’s end. The ending of this last fugue is sometimes heard with a melodramatic, petering-out texture, based on an incomplete sketch that survived among Bach’s scores. But given the hypothesis that Bach had indeed completed the fugue, at least in his mind, it seems dishonest to dramatize the sad fact of his death in this way. A number of musicians have attempted to compose a convincing ending, with varying degrees of success. These performances leave the listener with, one hopes, the appropriate question-mark — his son’s suggested half-cadence.

Bach’s organ chorale prelude based on the chorale “Vor deinen Thron tret’ ich hiermit,” (“Before thy throne I now appear”) was one of the last things Bach, now blind, dictated from his deathbed. It was not part of The Art of Fugue, and not a new work, but rather a reworking of a chorale prelude he had composed years earlier: “Wenn wir in höchstens Nöten sein” (“When we are in greatest need”). It was published at the end of the first, posthumous edition of The Art of Fugue. No doubt the editors, especially his son C.P.E. Bach, thought it a way of rounding out the supposedly unfinished project. Though not intended by his father as part of The Art of Fugue, we think it a fitting postlude.

Daniel Stepner (c)2018