Robert and Clara Schumann’s devotion to each other is legendary. Much of his music was composed with her in mind. And she championed his music throughout his short life and beyond.

Nine years younger than Robert, Clara had been a child prodigy, trained strictly by her piano-pedagogue father Friedrich Wieck, who seems also to have been the ultimate stage mom. (Her real mother had left him after providing him with five children, and the five-year-old Clara was only to reestablish closeness with her years later.) Wieck drilled his daughter from an early age, determined to make her the supreme example of his rigorous teaching methods. He pushed her into the public eye, managed Clara’s early career (representing her as younger than she really was), and strove to clear her young life of any distractions that might interfere with her musical training. Fortunately, her talent was up to his challenges.

At the age of 20, Robert Schumann studied piano with Wieck and also became a favored student. But when it became obvious five years later that Robert was courting the sixteen-year-old Clara, the jealous father pulled no punches in his violent resistance to the match. He forced their separation for four years, constantly pointing out Robert’s roller-coaster mood swings to her. He threatened Clara with disinheritance, he publicly denounced Robert, and he even instigated court proceedings, which ultimately failed. The couple married as Clara turned 21. Some of Robert’s most inspired songs came out of this fraught period.

Their marriage was not an easy one, mostly because of Robert’s volatility and the very unequal marketability of their gifts. He was not yet an established composer, while she was already a sought-after soloist. Yet they remained devoted to each other through many emotional trials, among them the parenting of eight children, and Robert’s descent into fatal psychosis. She became the family’s principal bread-winner with her frequent concert tours, often playing Robert’s music as well as music of their friends Mendelssohn, Chopin and Brahms. She was also known as an important interpreter of Mozart. Robert was to become a prolific composer but also an increasingly troubled man, with symptoms we would now call severely bipolar, delusional and psychotic.

Both Clara and Robert kept diaries (now published as “The Marriage Diaries”) that allow us to follow the ups and downs of their lives. During Robert’s tragic final breakdown and the two-year hospitalization preceding his death at the age of 46, she continued to concertize and provide for her family. After his death, she and her loyal friends Johannes Brahms and Joseph Joachim secured Robert’s legacy by presiding over a complete edition of his works.

As one can easily imagine, Clara had precious little time to compose, but she reveled in it when she did. She wrote: “Composing gives me great pleasure… there is nothing that surpasses the joy of creation, if only because through it one wins hours of self-forgetfulness, when one lives in a world of sound.” At another time she wrote: “There is nothing greater than the joy of composing something oneself and then listening to it.”

Of her compositions, Robert wrote: “Clara has composed a series of small pieces, which show a musical and tender ingenuity such as she has never attained before. But to have children and a husband who is always living in the realm of imagination, does not go well together with composing. She cannot work at it regularly, and I am often disturbed to think how many profound ideas are lost because she cannot work them out.”

Later in her life she wrote: “I once believed that I possessed creative talent, but I have given up this idea; a woman must not desire to compose – there has never yet been one able to do it. Should I expect to be the one?” Perhaps she knew nothing about women of the 17 th and 18 th centuries who did indeed compose (very little of their work was published). At any rate, in addition to being a pioneering female soloist, she left us a good deal of wonderful music, including many songs, music for solo piano, chamber music, and a piano concerto.

During her life most of her music was played only by herself and friends, and was largely forgotten until a resurgence of interest in the 1970s – three-quarters of a century after her death. Since then, however, her compositions have been performed frequently and many have been recorded.

Clara’s instrumental chamber works consist of tonight’s, Op. 17 (1846) and the Three Romances for violin and piano, Op. 22 (1853). She composed a number of solo piano works with the title “Romance,” but the Romances forviolin and piano were the only one set for more than one instrument. Composed as a birthday gift for Robert, they are real chamber music in the sense that the instruments are equally weighted – partners in a dialogue. The first Romance briefly quotes a melody from one of his violin sonatas, then only two years old.

The Trio is her only classically-cast work in four movements. It was clearly a major effort on her part, given her familiarity with the trios of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert and Mendelssohn. Interestingly, Robert hadn’t composed piano trios before Clara wrote hers, but in the few years following he composed three.

Clara’s Trio has many interesting features. One is her choice for a second movement of a gentle, classical minuet rather than an impish scherzo, which was more typical of the recent symphonies and chamber music by Schubert, Beethoven and Mendelssohn. Another is the lyrical, somewhat melancholy principal theme of the substantial last movement. These may explain her own later negative assessment of the Trio — “effeminate, sentimental” — which doesn’t ring true to this player, at least. The Trio is full of beauty, romantic thrust, strong structural fiber and admirable internal development. It reflects great musical intellect, contrapuntal skill, and conciseness of expression.

Robert Schumann was deeply involved with the romantic literature of his day, and even considered becoming a novelist in his youth. Though he turned decisively to composition in his early twenties, he went on writing music criticism and appreciations of colleagues throughout his life. Papillons, his Op. 2 shares a programmatic element inspired by the novel Flegeljahre (Adolescent years, by Jean Paul) with his better-known suite Carnaval, Op. 9. Both were inspired by masked balls, and the psychological intrigue behind the masks. Carnaval famously features two movements – Eusebius and Florestan — that Schumann thought represented the two poles of his own personality, the former his calm, deliberative side and the latter his impetuous, mercurial aspect. Other movements in Carnaval are entitled Chiarina (Clara), Chopin and Paganini. Still others are coded references to other people in Schumann’s life, and to Commedia del arte characters.

In contrast, the movements of tonight’s Papillons (Butterflies) and Märchenbilder (Fairy tales) are non-specific, and yet they evoke their titles’ meaning. Papillons consists of a short introduction (an invitation to the dance?), and then nine short, whirling waltzes, interspersed with two polonaises (a slow Polish dance, also in ¾ time) and a finale (“Grandfathers’ Dance”), closing with an evocation of bells, signaling the end of the masked ball. As in Märchernbilder, the listener is implicitly charged with imagining what sorts of characters each of the movements portray.

Robert composed prolifically in intense periods, punctuated by bouts of melancholy and torpor. The year 1842 in Robert Schumann’s life is sometimes called “the year of chamber music” by his biographers. Having already composed the first of his four published symphonies and dozens of songs, he turned to large-scale instrumental chamber music. That year saw the birth of his three string quartets, his Fantasy-pieces for piano trio, his perennial favorite Piano Quintet, and tonight’s Piano Quartet Op. 47 (composed in one month!). Its energy, variety, and lyricism bespeak the catharsis of an inspired mind. A few notable features include the quiet mystery of its

introduction (which returns in the middle of the otherwise animated and athletic first movement), the evocation of the Brothers’ Grimm-like goblins of the second movement, the breathtaking lyricism and nod to late Beethoven of the

slow, third movement. This movement’s final bars foreshadow the vehement finale, which is full of imitative counterpoint and harmonic adventurism.

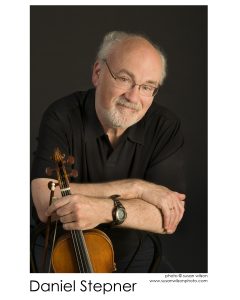

Daniel Stepner ©2022