As Stravinsky once said, “Good composers borrow – great composers steal.”

As Stravinsky once said, “Good composers borrow – great composers steal.”

Like most future musicians (I suspect), I have had a lifelong interest in noisemaking. Before the introduction of instruments, which eventually channeled this energy in a specifically musical direction, I enjoyed shouting, banging, and using household objects as makeshift percussion equipment (all of this is well-documented on VHS tapes residing in my parents’ basement). I started experimenting with composition when I was six or so – as soon as I understood the basics of reading music. Probably the best that could be said about these early “compositions” is that my handwriting was not as illegible as one might expect.

My first time ever performing was as part of a handbell choir. I was five. The conductor assigned me the two smallest, highest-pitched bells, and (because I was just starting to learn to read music) promised to point at me when it was time for me to play. In the heat of the moment, however, she forgot to point – so I remained silent and motionless through the entire piece. In essence, the first performance of my life was a non-performance. My parents were very confused.

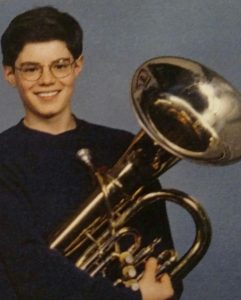

From as far back as I can remember, my parents exposed me to music in a variety of styles, from Bach to the Beatles to Queen. When I first expressed interest in performing they encouraged me. And as I took up more and more instruments – first viola, then euphonium, then drums, and finally piano – I was fortunate to enjoy their full support. Between church ensembles, school ensembles, and the occasional garage band, I spent a hefty percentage of my free time throughout childhood and adolescence playing music.

I originally enrolled in college as a creative writing major and music minor – however, by some fluke I was assigned nothing but music courses my first semester. As soon as I started to seriously study music theory, I realized that my creative impulse would be much more effectively channeled in a musical (rather than literary) direction. Since I was 18, I’ve never seriously considered being anything besides a composer.

I originally enrolled in college as a creative writing major and music minor – however, by some fluke I was assigned nothing but music courses my first semester. As soon as I started to seriously study music theory, I realized that my creative impulse would be much more effectively channeled in a musical (rather than literary) direction. Since I was 18, I’ve never seriously considered being anything besides a composer.

Historically, it’s hard to find first-rate composers who were also first-rate teachers. Amazingly, I was lucky enough to study composition with three gifted, generous teachers whose music I also greatly admire. Jimbo Walsh (at Loyola University New Orleans), Mark Stambaugh (at Manhattan School of Music) and Reiko Fueting (also at MSM) are widely disparate artists whose single similarity is a great commitment to their students. These three composers stand out as mentors; but of course I owe a debt to every teacher who shared their expertise with me at any stage of my development. To Kate Myers, who spent two (presumably unpleasant) years teaching me the rudiments of brass technique – God bless you, madam.

Every type of music inspires me, in the sense that every musical work has something useful to teach. I love the process of listening deeply – noting what appeals to me and what does not (and storing that knowledge away to use later in my own work). I grew up listening to and playing lots of rock and heavy metal, and continue to listen to that alongside art music. Some of my favorite canonical composers include Bach, Beethoven, Berg, Varese, Messiaen and Reich, and in their works I find much to emulate.

The great thing about composition is that, when I hear something interesting in a piece, I can go examine the score and see exactly how it was done. As Stravinsky once said (perhaps apocryphally): “Good composers borrow – great composers steal.” Expanding your vocabulary means constantly seeking out and absorbing new sounds, structures and techniques.

I’ve always had a very strong and irrepressible need to create. In addition to composition, I devoted large parts of my childhood and teen years to creative writing, visual art, and photography. Whenever I was given a choice between the creative and interpretive sides of a discipline, I was always drawn more towards the former: for example, I tried acting, but preferred writing plays. Likewise, although I was successful as a musical performer, I was always drawn more towards composition. I’m not sure why this is, but I know that I find the process of artistic creation – something from nothing, so to speak – unbelievably exciting.

That being said, I work hard to maintain outlets for performance. Nowadays, that mostly means conducting. I enjoy conducting because it couples the solitary and social aspects of music together: a good conductor must devote himself to hours of study, but be comfortable and confident enough in rehearsal/performance to unite a group of distinct personalities in the pursuit of a single object.

You can’t write for trio sonata without feeling the burden of history. So many masterful pieces exist for this instrumentation that, while writing, one often feels the great masters of the Baroque are looking over your shoulder. Additionally, because this instrumentation is associated so closely with a particular time period, one has to wonder: what, besides novelty, is the value of writing a trio sonata in 2016?

Ultimately, what drove the creation of Sonata/Sonare was two things. First, a personal association of the trio sonata with an quasi-analogous contemporary ensemble – the rock band. Growing up, I played drums in a variety of bands, and I was interested in projecting that collaborative spirit (and elements of the language of popular music) onto the trio ensemble instrumentation. Hopefully, the result evokes the rawness and excitement that must have pervaded the performance of this repertoire during its earliest days.

Second, I was intrigued by the term “sonata” itself. Derived from the Latin sonare, which means simply “to sound,” it is an expression that has become weighty with meaning, carrying with it expectations about musical form in particular. In the piece, I attempt to depict a journey away from these expectations, and towards a new means of formal organization.

I’m currently working as the conductor of ShoutHouse, a classical/hip-hop orchestra based in NYC. I’ve written for that ensemble several times, and it’s a real challenge to blend those traditions in a way that is engaging, sophisticated and respectful. In my opinion, the more opportunities I take to push outside the space typically allotted to the “normal” composer, the better understanding I gain of the craft.