Quartet in B Flat Wolfgang Amadée Mozart (1756-1791)

(an early 19th century transcription of Mozart’s Sonata, K. 317)

Allegro moderato – Andante sostenuto e cantabile – Rondo: Allegro

Trio in E Minor, Op. 38, No. 1 Bernhard Romberg (1767-1841)

Allegro non troppo — Andante — Allegretto

Intermission

Septet in E Flat, Op. 20 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Adagio / Allegro con brio — Adagio cantabile –

Tempo di Menuetto – Tema con Variazioni –

Scherzo – Andante con moto alla Marcia / Presto

* * *

Eric Hoeprich, classical clarinet

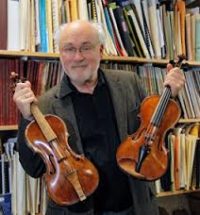

Daniel Stepner, classical violin

David Miller, classical viola

Jacques Lee Wood, classical cello

Todd Williams, natural horn

Andrew Schwartz, classical bassoon

Anne Trout, contrabass

~

Towards the end of his time in Salzburg (ca.1779), Mozart composed a series of brilliant instrumental works that may have contributed to the souring of his relationship with his employer, Prince-Archbishop Hieronymous Colloredo. The Prince-Archbishop expected Mozart to show particular concern for the musical needs of the cathedral and the court. While Mozart continued to do his job both as performer and composer, he was concurrently very preoccupied with writing works inappropriate for either venue, due to the secularity of the works and/or their demand on performers and listeners alike. It is widely believed that among these works was the violin sonata in B-flat, K.378.

By the end of 1781, it must have seemed to Mozart that he was right in moving to Vienna: he was the city’s finest pianist, proven so after a performance competition between himself and rival Muzio Clementi, staged by Emperor Joseph II. In addition, Mozart published six keyboard and violin sonatas, including K.378, and they were met with great praise. In particular, they were lauded for being “unique of their kind. Rich in new ideas and traces of their author’s great musical genius.”

The first movement is itself rich in melodic ideas; the exposition sets forth at least three important themes, which is unusually generous for classical style. The second movement bears a touching sentimentality, situating itself historically between the music of Johann Christian Bach (whom Mozart greatly admired) and the music of The Abduction from the Seraglio, which Mozart was soon to write. The last movement is a vigorous rondo written in triple meter, mostly, with an episode in quadruple meter.

The present arrangement for clarinet quartet is a testament to Mozart’s continued fame after his death in 1791. The arrangement was likely made by Johann Anton André (1775-1842). André was one of those figures in music history whose significance far outweighs his fame. Around 1799, he obtained Mozart’s known manuscripts, correspondence, etc. from his widow, Constanze, and her husband. His organization, cataloguing, and publication of this body of documents became his life work, though his success in the endeavor fell short. Nonetheless, his efforts paid off in the work of future scholars to the point that André might be called “the father of Mozart research.”

Among the works André published was the clarinet quintet, K.581, in its first, albeit corrupt, edition. He apparently believed there was a market for such pieces, as indicated in the correspondence between Mozart’s widow, and the publisher. In addition, many other composers were contributing to the repertoire, including Johann Nepomuk Hummel, Franz Krommer, Franz Anton Hoffmeister (who also published Beethoven’s septet), Johann Baptist Wanhal, etc.

For most Americans who know the name “Romberg” in a musical context, they are thinking of the composer of The new moon, The student prince, and The desert song. But that is Sigmund Romberg (born Rosenberg). Bernhard Heinrich Romberg was a composer, but also one of the most important cellists in the history of the instrument. He developed and mastered new techniques for the cello, learning not only from cellists in the great late–18th-century orchestra at Mannheim, but also from the contemporary violin virtuoso Giovanni Battista Viotti. Throughout the latter half of his career, his fame as a cellist extended across the continent, from Spain to Moscow.

This trio by Romberg is the first of a set of three bearing the name Trois trios d’une difficultée progressive pour le violoncelle avec viola et basse. (Three trios of progressive difficulty for violoncello, with viola and bass). The date of these works is not clear, though an 1824 German publication identifies them in a new publication. The trios really do get progressively more difficult: the last trio filled with rapid figures and technical fireworks. Even the last movement of this trio is not for the faint of heart.

It will be immediately clear that these works are all about the cello, not surprisingly. The lower-ranged accompaniment (viola and contrabass) facilitates that dominance. The E minor tonality gives a melancholic flavor to the opening movement, with its one distinctive theme. The second theme of this sonata form is triplet figurations. In the development, the viola and bass are allowed a lyrical moment over virtuosic arpeggiations in the cello. The Andante grazioso, a brief aria in ABAB1 form (the second half repeats the first, with some variation), is in C major. The finale is a rondo-like movement, with the second episode more developed than the first. A Schubertian pathos presides, partly because it never fully shakes minor mode. This gorgeous gem is a window into the musical diversions of the early 19th century.

By the way, during a stint in Bonn, Romberg played in the orchestras of the court and the theatre, where there he met a young violist named Ludwig van Beethoven; Romberg would later premiere the sonatas, op. 5, by the same composer.

“Burn this septet.” These are the alleged words, or something akin to them, uttered by Beethoven later in his career, after witnessing the unyielding popularity of the final work on our program. It was not so much that he necessarily disliked the septet. Rather, it represented to him a conventional approach to composition. As may be seen in almost anything he wrote after 1800, he relished new ideas, and new ways of working with those ideas. Understandably, Beethoven would have preferred that appreciation of his latest efforts equaled the popularity of earlier work. To be sure the septet, op. 20 is a classic example of late–18th-century style, yet it is injected with unfamiliar levels of virile energy, when compared to even the works of Haydn, or other contemporaries.

In November 1792, Beethoven moved to Vienna permanently, at the age of 22 (Mozart was 25 when he had done the same). He studied with Haydn and Johann Albrechtsberger, and was making other valuable contacts. One of the most fruitful of these contacts was Ignaz Schuppanzigh, a violinist frequently engaged by Beethoven’s future patron, Prince Karl Lichnowsky. The prominence of the violin in the septet points to Schuppanzigh’s impressive talent.

The septet, completed in 1799, is in six movements—an oddity in late–18th-century repertoire, but not unique. Historians note that it is reminiscent of the divertimento genre, of which Mozart and Haydn wrote a few. In fact, Beethoven appears to have taken Mozart’s divertimento, K.563 for string trio (performed by Aston Magna last summer) as a model. It also has six movements, ordered exactly the same as Beethoven’s septet, and in the same key. Nothing in this observation diminishes Beethoven’s achievement: he had come across an unusual and inspiring model and strove to match its brilliance.

Beethoven begins the opening movement with a slow introduction. The body of the sonata-form movement is initiated by the string trio, and is overflowing with motivic ideas and quick contrasts of gestures (rhythms, articulations, etc.). The expansive Adagio cantabile, with its compound triple meter and prominent wind parts, hints at the slow movement of the Pastoral symphony, still a decade down the road. The theme of the Tempo di Minuetto is taken from the earlier keyboard sonata in G, op. 49, no. 2. It is a bit of a delight to hear how Beethoven delegates the different voices. The theme of the variations is a march that he subjects to five variations and an extended coda, with a bit of Haydnesque tease in the final measures. The spry scherzo features some virtuosity in the violin while the Trio of the scherzo is given over to some lyrical cello sounds. The finale begins with another slow introduction, this with a decided tilt towards the parallel minor. Again, a sonata form at a vigorous tempo unfolds in the body of the movement with some extras thrown in, including an inexplicable cadenza for the violin at the end of the recapitulation, causing the listener to wonder whether this was a violin concerto all along.

Beethoven (“humbly and obediently”) dedicated the septet to Empress Maria Theresia, second wife to Emperor Franz. It was premiered as part of a famous concert on April 2, 1800 that also included a symphony by Mozart, a concerto and a symphony by Beethoven, two arias from Haydn’s Creation, and improvisations by Beethoven. At this early stage, Beethoven seemed rather proud of the septet. While there were several arrangements of the work, from which he generally distanced himself publically, there is one he wrote himself a few years after the septet: a trio for clarinet (or violin), cello, and piano, op. 38.

–Joseph Orchard © 2018