In a soaring review of Aston Magna’s opening season concert in Hudson, N.Y., The Millbrook Independent’s Kevin McEneaney walks us through a compelling evening.

A few excerpts:

“…this chaconne by Purcell is so personal in voice and so movingly melancholy that it remains shocking and here Stepner’s violin was at the height of eloquence in the finale of the single movement.”

“…Jason Fisher’s viola which could finger and bow as quickly as the violins.”

“Stepner illustrated how the string quartet reached a level of adamant perfection. Often nicknamed “The Rider” or “The Horseman” for its racing fourth movement, it remains one of Haydn’s most favorite audience pleasers. Here Stepner was on fire—they all were!—as they achieved an almost orchestral sound from four strings.”

Read the review on The Millbrook Independent website, or below.

ASTON MAGNA PONDERS MODERNITY

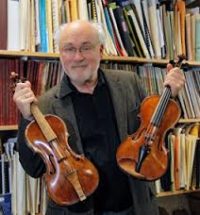

From left: Daniel Stepner, Jason Fisher, Jacques Lee Woods, Julie Leven

Warm summer weather is here and that means that the Aston Magna Summer Festival is also here. They began their season by looking back into the origins of the string quartet with the promising title of “The Birth of the String Quartet.”

The quartet opened with Dario Castello (1621-1658), a forward-looking Venetian prodigy who was already composing at the age of eight. We don’t have any idea of how many compositions he wrote in what he called the “modern style,” yet we do have twenty-nine of his compositions, and, yes, he is moving away from the simple Medieval style. The quartet developed out of the trio and it was Castello who empowered the bass with an independent figuration, which cellist Jacque Lee Woods ably intoned. This counterpoint undertow endowed the composition with great excitement. As in Irish-English folk music the two violins and viola rounded upon repeating refrains with intense energy after brief digression, while the circularity of Medieval musical time predominated in what is today labeled Celtic music, which is really the old European music, especially beloved in the kingdom of Lombardy. That lively dance-genre music was propelled into abstraction and no longer danceable: we were on the horizon about to leave circular time behind. Castello is not exactly a household name and I have only ten of his sonatas on disc, but not No. 16, which was played with such vivid unity.

In his introductory talk Daniel Stepner declared this Chacony by Henry Purcell (1659-1695) to be his favorite of all Purcell’s works, a rather intense claim. While the chaconne originated somehow in Latin America and brought to Europe through Spain, its triple meter was an attractive extroversion. In general, English music lacked both individuality and especially pathos because of its addiction to the simple syncopation of the Trochee (stress, unstress) that predominated in English songs and music as in John Dowland who is thought to have written most of the music for Shakespeare’s plays. Of course, it was the countering triumph of the Staffordshire accentual preference for the iamb (unstressed, stressed) that conquered the Elizabethan stage. In any case, this chaconne by Purcell is so personal in voice and so movingly melancholy that it remains shocking and here Stepner’s violin was at the height of eloquence in the finale of the single movement. It would be centuries before a native English musician could rise to the stature of Purcell.

Antonio Caldara’s Sonata a Quattro IV lifted us up to two movements, the first being mildly sad, but followed by a cheerful Andante. George Philipp Telemann’s Quartet in A major brought us up to the three-movement division popularized by Antonio Vivaldi yet it was not the fast-slow-fast formula patented by Vivaldi but slow with feeling, then more lively, and then really fast. Here second violinist Julie Leven excelled. Frantisek Xaver Richter’s Quartet, Op. 5, no. 1 in C major employed Vivaldi’s three movement formula while allowing all instruments to have their individual say, including Jason Fisher’s viola which could finger and bow as quickly as the violins.

The vague beginnings of the quartet were codified by Franz Josef Haydn (1732-1791). His early Divertimento in E flat (Quartet, Op. O) was not discovered until the 1930s which is how it was marked zero. While it follows the fast-slow-fast recipe of Vivaldi, there is that density of planning which we have come to expect from good chamber music. Haydn wrote symphonies for income and chamber music for his friends, yet his heart was really with the exciting crossing lines of the chamber music experience. We were now entering the intricacies of modern chamber music.

It did not surprise me that my box set of Mozart: Complete String Quartets did not contain K. 156 because the word complete is the most misused word in music packaging. But that is one of the many reasons a concert fanatic goes to concerts: to discover the overlooked gem, which is what the Artistic Director, Daniel Stepner, programed for this occasion. This quartet was one of six that Mozart composed on his third journey through Italy. He was influenced by Giovanni Battista Sammartini from Milan. Unlike the static cycle of Castello, Mozart’s cycles plunge ever downward and the concluding Menuetto threatens to halt completely yet comically moves on to stilted conclusion. Later, Mozart repeats this jocular trick in String Quartet in F major, K. 590 in a 1789 plea to King Wilhelm II for payment but it appears he was never paid. And it doesn’t appear that he was paid for these six Italian quartets.

In concluding with Haydn’s Quartet in G minor, Op. 74, no. 3 Stepner illustrated how the string quartet reached a level of adamant perfection. Often nicknamed “The Rider” or “The Horseman” for its racing fourth movement, it remains one of Haydn’s most favorite audience pleasers. Here Stepner was on fire—they all were!—as they achieved an almost orchestral sound from four strings. Despite the extroverted conclusion, this piece bears the unmistakable sound of Haydn’s voice: chamber music is no longer merely a private exercise of the artist—it is the private exercise of art in a public context! And that is real modernity!

Next Friday Aston Magna performs at Wethersfield Gardens. For a preview of this exciting concert click here.

Read the full review here.