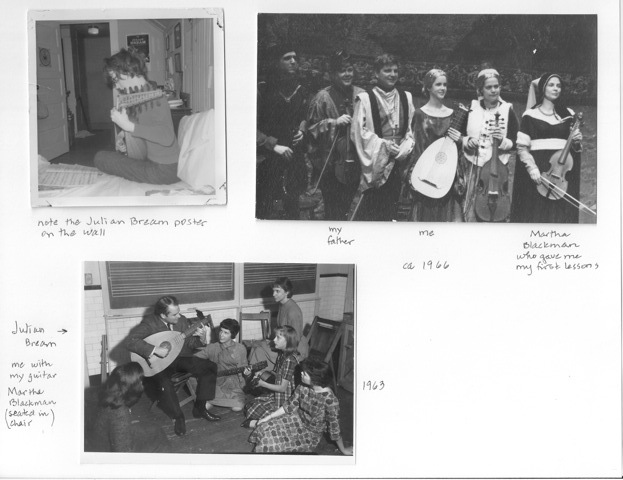

When I was in 7th or 8th grade, my father brought home a recording called “An Evening of Elizabethan Music” performed by the Julian Bream Consort. I fell head over heels in love with the music. I played the record until the grooves were gone! The tunes, the rhythm, the sound of the lute weaving in and around the other instruments…having this interest kept this shy teenager from being completely swallowed up in a high school class of over 450 students. Whatever they all were doing, I had my lute

You could say that my formative years were all about music — first on piano (3rd grade), then viola da gamba (8th grade), then lute (9th grade), then organ (10th grade). In fact, I don’t know how I would have gotten through my formative years without it. I had my first lute in 10th grade (I started on a borrowed lute), and I was studying organ then, too. So I had no time to think about what would make me popular, what clothes I “should” be wearing, what radio station I “should” be listening to. It was Julian Bream for me, all the way!

I just kept studying, on through college at Sarah Lawrence College, and then after that at the Schola Cantorum in Basel, Switzerland. And then performance opportunities. And more concerts. And teaching. And I’m still at it.

I had several mentors: the first was Martha Blackman, who herself was a viola da gamba player, but she had a colleague or two in New York Pro Musica who gave her some tips on how to teach lute. From her I mostly learned about musicianship, and playing in a musical way. She also channeled performance opportunities my way, which gave me some important early experiences. Suzanne Bloch was another very encouraging teacher. And my teacher in Basel, Eugen Dombois was very inspiring and supportive of the musician I was becoming.

The unique niche of early music — it was discovered for me as my parents, my father in particular, was pursuing his own interest in early music. These were the recordings we heard as kids. The concerts he took me to were all early music: New York Pro Musica, Julian Bream, the Early Music Quartet. Those became my soundworld. In that climate, playing the lute was a normal, logical choice.

The unique niche of early music — it was discovered for me as my parents, my father in particular, was pursuing his own interest in early music. These were the recordings we heard as kids. The concerts he took me to were all early music: New York Pro Musica, Julian Bream, the Early Music Quartet. Those became my soundworld. In that climate, playing the lute was a normal, logical choice.

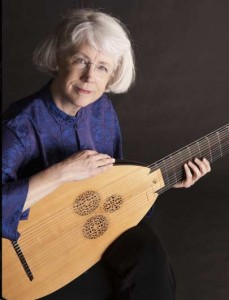

Then came the theorbo: if you play the lute; if you love to accompany the voice; if you love 17th century music, then you probably either have a theorbo already or you have one on order. I didn’t know what a theorbo was until I went to study at the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis in Basel, Switzerland. That’s where I met both the repertoire and the instrument. One does not have to have a theorbo to accompany this repertoire, but there are a few descriptions in treatises saying that it is the ideal instrument to accompany the voice, and in fact it was developed from the lute for that express purpose: it has a sweet, yet resonant sound, not pushy but present.

As unusual looking as the theorbo is to us today, it really was the favored instrument for accompanying the solo voice in the 17th century because of its own expressive possibilities, being plucked by fingers rather than quills.

Catherine Liddell is a longtime member of the Aston Magna Music Festival ensemble, a renowned player of the lute and theorbo.