We violinists need to be reminded occasionally that historically we were interlopers in the realm of “serious,” cultured instrumental music, of which the regal gamba was emblematic. Writing about the brash newcomer in Epitome musical (1556), composer Philibert Jambe de Fer described the differences between the viola da gamba (viola of the leg) and the violin (“viola da braccia” – of the arm) in great detail. After noting the more obvious (the numbers of strings, tunings, frets or no frets, bow-grips), he went on to say: “The form [of the violin] is smaller, flatter, and in sound it is much harsher. It is easier to carry, a very necessary thing while leading wedding processions or mummeries. I have not illustrated the said violin because you can think of it as resembling the viol, added to which there are few persons who use it save those who make a living from it through their labors.”

This last, dismissive comment is telling. Obviously, the lowly violin was first employed by those who tried to “make a living” with it, playing in taverns, at wedding dances and parties – in other words background music that could nevertheless be heard through the din of banter and dancing feet. In contrast, the older, more soft-spoken gamba had attained the status in this period of a proper instrument for cultured amateurs, who played for each other and for serious, attentive listeners. The sound of the gamba was often compared to the human voice, presumably of the soave, middle range!

The simpler, ruder violin appeared barely a generation before Jambe de Fer’s put-down. In addition to its penetrating acoustic qualities, its construction (overlapping edges, fewer strings) began to attract instrument makers, and by 1580, members of the Amati family and others were turning out carefully made violins of all sizes. Unlike most instruments – winds, keyboard and plucked stringed instruments — the violin family (including the viola and cello) has remained relatively unchanged in its essential structure since the beginning of the 17thcentury. Yet its story is complex and fascinating. The challenge of creating the perfect violin started early on: since Antonio Stradivari (1644-1737), that obsession has continued to this day.

The violin was quite quickly domesticated, heard more and more frequently at court, and over the course of two centuries it eclipsed the gamba as a serious instrument one studied and listened to. The two families coexisted during this transitional period, and many composers (including Monteverdi, Buxtehude, Marais, Couperin and Bach) wrote music explicitly for the two types together in one composition. But while the gentle gamba came to be associated more and more with the aristocracy, the audacious violin was more widely played by all levels of society. In 16th and 17th-century England, playing the gamba flourished as a middle-class gentleman’s pastime, but even here the violin encroached. In 1676, composer Thomas Mace wrote in his Musick’s Monument that the gamba’s effect was the “dispossessing the soul and mind of all irregular disturbing and unquiet [e]motions, and still and fill it with quietness, joy and peace, absolute tranquility and inexpressible satisfaction.” Whereas (he wrote later), “Observe with what wonderful swiftness they [the violins] now run over their brave new airs, and with what high-prized noise, viz., ten or twenty violins, etc…. to some single-souled ayre and such-like stuff, seldom any other, which is rather fit to make a man’s ears glow, and fill his brains full of frisks, etc., than to season and sober his mind, or elevate his affections to goodness.”

Despite this rearguard protest, the violin flourished, especially in Italy, where players, makers and composers helped to make it a central instrument in both church and secular music. From there (thanks in part to advances in music publishing and the valuing and export of Italian violins) it captured the world’s heart, and there are few places in the world today that do not boast some sort of violin.

The gamba, by contrast, virtually disappeared in the late 18ththrough mid-20thcentury, despite a few valiant antiquarian efforts to resurrect it. Its real resurgence started after 1950, and paralleled the return of the harpsichord and earlier forms of wind, percussion and stringed instruments. One of the prime movers in the renaissance of the gamba was John Hsu (1931-2018), who performed and edited much of its large repertoire. John was Artistic Director of Aston Magna from 1985-1990. We dedicate this concert to him (see the detailed tribute elsewhere in this program book). His complete edition of the voluminous music of Marin Marais is a fitting monument to Marais — the dean of solo gamba music — as well as to John himself.

* * *

The Venetian composer Dario Castello (ca. 1590-1658) was probably a wind player, but published a collection called Sonate Concertatein 1629, with designations for a variety of instruments, though many of the upper parts could be played by violin, recorder, or cornetto. Sometimes he specifies bass instruments: dulcian (early bassoon) or sackbut (early trombone). His music helps bridge the early canzona style, with its short, contrasting sections, to the emerging sonata forms, with their more lyrical lines and their recitative-like passages for one instrument, alternating with ensemble passages that are imitative, and others in which the instruments move as one.

Venetian born Antonio Caldara (1670-1736) was active in Venice a century after Castello, first as a chorister at St. Mark’s Cathedral, but he also worked and lived in Mantua, Barcelona, Rome and Vienna, where he died. He was a prolific composer, producing 100 operas, and many oratorios, cantatas, madrigals and instrumental works.

In the late 17thand early 18thcentury there was a pitched battle between advocates (mostly opera-lovers) of French versus Italian trends in music. Both Jean-Marie LeClair and François Couperin, prominent French musicians, saw the value in synthesizing the best of both worlds. As a young composer, Couperin was taken with Italian instrumental attitudes and forms, but so great was the partisanship: he couldn’t publish his own earlier works in the Italian style under his own name. He did so under the name of Pernucio – an anagram of Couperin. Later he could admit it publicly. He composed a large repertoire for his own instruments: organ and harpsichord, and a smaller but highly polished set of chamber works, including the two fanciful, sublimated mini-dramas: “The Apotheosis of Lully,” and “The Apotheosis of Corelli,” which combined the formerly contentious styles in a gracious suite, the titles of which describe the decorous peace-making and progressive musical integration of French and Italian styles, in the Elysian Fields, no less.

Lyon-born Leclair was a professional dancer and a master violinist. He composed several sets of ground-breaking violin sonatas, trio sonatas, many violin concertos, and a substantial set of sonatas for two violins without any accompaniment. Unlike Couperin, Leclair rarely titled his works, but he was clearly interested in integrating French and Italian styles in absolute music. His life was cut short when he was murdered at age 67.The murderer was never identified or caught, though family intrigue is suspected.

Few details of the life of aristocrat Ste. Colombe are known, including his birth date. He was a celebrated master of the viola da gamba, known for his eccentric style of playing, which comes through in the music he composed. It shows an understanding of the sonorous possibilities of the gamba, but is full of awkward compositional details. We do know that he taught the young Marin Marais, who memorialized Ste. Colombe in an elegy, the Tombeau de Ste. Colombe.

TheTombeau Les Regretsby Ste. Colombe himself is a programmatic elegy. An opening lament is followed by the evocation of bells (Quarrillon), followed by the Call of Charon, the boatman who rows the dead to Hades, followed by Les Pleurs (the melancholy tears of the dead) and finally the joy of the reaching Elysian Fields.

Robert de Visée excelled as guitarist, lutenist and theorbo player. Like Marais and Couperin, he often played at the court of Versailles and composed a small but distinguished body of works for his instruments.

Of humble birth, Marin Marais rose in the world to become Ordinaire de la chambre du Roi pour le violeat the lavish court of Louis XIV. This allowed him to become a consummate player and a prolific composer for his instrument. Marais’ playing became legendary, and he created a rich and varied legacy with his five books of “Pièces de viole,” that has become the central body of work for the gamba player of today. Besides the nearly 600 movements that comprise these books, he composed many trio sonatas, and a major set of works for violin, gamba and continuo, and four operas.

The cryptic title of Couperin’s solo harpsichord piece,Les Barricades Mysterieuses, has resisted definitive interpretation for centuries, but the piece itself has become a perennial favorite with harpsichordists and audiences, and has been arranged by many musicians for myriad instruments. (It has even figured prominently in several movies, including Terence Malick’s recent The Tree of Life).

Similarly, we don’t know why Couperin chose the title “La Sultane” for his only sonata in four voices. There is nothing “Oriental” about the rhythmic or harmonic language of the work. Perhaps the striking richness of the texture (two treble instruments, two gambas and continuo) suggests something exotic. And the culture of the Ottoman Empire held fascination for several generations of composers, from Vivaldi, Rameau and Couperin through Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven and beyond. At any rate, “La Sultane” is characterized by a richness of development as well as sonic texture. There are fewer movements than in Couperin’s other chamber music, but they are longer and more varied. The gambas sometimes double the bassline, but often they break free and are heard as a duo of tenor voices above the bass, and sometimes as a duo dialoguing with the violins. Couperin makes wonderful use of the combinatorial possibilities. Once again, Couperin is integrating musical styles, as well as instruments of different registers. Could he have been subliminally yearning for an East-West détente?

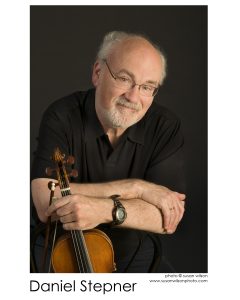

~ Daniel Stepner (c)2018

~ Daniel Stepner (c)2018

.