A composer from the mists at Aston Magna: Elisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre

A composer from the mists at Aston Magna: Elisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre

GREAT BARRINGTON — If you delve far enough into baroque music, there’s always a composer you’ll encounter for the first time.

Aston Magna came up with Elisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre — a woman, no less — at its winter concert Saturday in Saint James Place. Without a printed program to identify the composer of her sonata, you might have guessed Corelli. And indeed, the Frenchwoman (1665-1729) was an almost exact contemporary of the Italian master (1663-1713), who preceded her on the program.

It turns out Elisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre — she took the warlike surname from her husband — was a well-known harpsichordist and composer in the court of Louis XIV. Her sonata, one of nine selections performed by the Aston Magna ensemble of five, was a pleasant trifle, noteworthy for her use of echo effects.

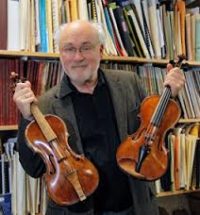

For its annual cold-weather visit, the summer early-music festival brought tenor Frank Kelley, violinists Daniel Stepner and Julie Leven, gamba player Laura Jeppesen and theorbo player Catherine Lidddell to the Berkshires. The offerings ranged from the tepid (a Rameau cantata recalling Orpheus’ travails in the quest for Euridice) to the vivid (an elaborate chaconne by Purcell).

The instrumental ensemble, as usual in this series, played clearly, thoughtfully, even exuberantly. Especially in the Purcell chaconne, Stepner and Leven proved interestingly matched violinists, exchanging expressive touches and tone qualities, a little like birds cheerfully singing back and forth to each other. Jeppesen, whose long-necked lute stood in for a more customary keyboard instrument in the continuo accompaniments, frequently made the viola da gamba a modest but eloquent soloist.

The program opened with a minor mystery: Antonio Bertali’s “1,000 Gulden” Sonata. Why was this piece, which was over almost as soon as it started, worth 1,000 gulden? And how much was a gulden worth anyway?

The best available answer: The sonata is one of a group published by Bertali, perhaps for that sumptuous payment.

Music of more substance was to come, beginning with “Plainte” and “Les Voix Humaines,” both instrumental, by Marin Marais (yes, he of the film “Tous les matins du monde”). The former was aria-like, the latter steeped in melancholy, with sighs from the gamba. Kelley sang a madrigal by Monteverdi, “And is it then true, heartless and cruel spirit,” its conventional sentiments summed up in dire wisdom: “The wise lover is always master of his impetuous desires.” Take it easy, Orpheus.

Three selections from Handel’s “Messiah” — “How beautiful are the feet of them that preach,” the Pastoral Symphony and “Ev’ry valley — closed the program.

Kelley sang intelligently and navigated the showy, high-flying lines of “Ev’ry valley” heroically. But in both Handel and the Rameau and Monteverdi selections heard earlier, his clarion voice was limited by intermittent signs of wear. And four soft-spoken stringed instruments, however valiantly played, don’t quite add up to a full orchestra in celebratory mood in Handel’s seasonal favorite.

Andrew L. Pincus reviews classical music for The Berkshire Eagle.